[Two obituaries of one man, written like all such pieces against a background feeling of shock and upset, while trying to cope with the recently received dire news. The first of these memoirs is about the science fiction and fantasy writer Richard Cowper, and was written at high speed in something of a state of shock a few hours after the news broke. It was published within a day or two in Dave Langford’s Ansible . The second is a more formal piece, written as a newspaper obituary of John Middleton Murry, Cowper’s real name and identity. CP knew him as both. These articles may be downloaded, but may not be uploaded or printed elsewhere.]

Richard Cowper

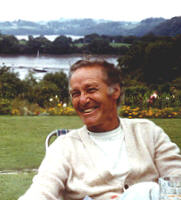

I met Richard Cowper (John Murry) at the first British Milford writers’ workshop, in 1972. It was his first contact with the sf world, ever. He stuck it gamely for a day, then slunk away somewhere. I found him in a tiny TV lounge, horizontal on a couch, a ciggie smouldering in his fingers, a story about a dragon folded across his chest. We began talking, united by our irritation with the inane writing of one particular famous author who was present. Our friendship started then. Nearly thirty years have passed since, my estimation of him, both as a man and as a writer, growing year by year. I loved the mischief in him, the way he could play the giddy goat, his funny gossip, his rage at the idiots around him – but also I respected him for his seriousness and passion about books and writing, the extent and depth of his reading, the skill and emotional impact of his novels, the adoration he had for his wife Ruth and his two daughters, Jacky and Helen. A capable man, he could plant a wood, sail a boat, restore antiques, grow tobacco, rail at critics, sweep a chimney in two seconds flat. His fiction was never given the critical reception it deserved, though the books were popular with readers. Fifteen years ago he suddenly gave up writing, exhausted, he said, of things to say. He took up painting instead and repaired Victorian chairs. At the end of March this year, after fifty years of marriage, Ruth died after a long illness. At her funeral Richard read a paragraph from his autobiography, describing his love for her at first sight. It was a stunning moment in the quiet chapel, charged with love and an aching sadness. Just under four weeks later he died too, suddenly and shockingly. His heart was broken, his daughters say.

I met Richard Cowper (John Murry) at the first British Milford writers’ workshop, in 1972. It was his first contact with the sf world, ever. He stuck it gamely for a day, then slunk away somewhere. I found him in a tiny TV lounge, horizontal on a couch, a ciggie smouldering in his fingers, a story about a dragon folded across his chest. We began talking, united by our irritation with the inane writing of one particular famous author who was present. Our friendship started then. Nearly thirty years have passed since, my estimation of him, both as a man and as a writer, growing year by year. I loved the mischief in him, the way he could play the giddy goat, his funny gossip, his rage at the idiots around him – but also I respected him for his seriousness and passion about books and writing, the extent and depth of his reading, the skill and emotional impact of his novels, the adoration he had for his wife Ruth and his two daughters, Jacky and Helen. A capable man, he could plant a wood, sail a boat, restore antiques, grow tobacco, rail at critics, sweep a chimney in two seconds flat. His fiction was never given the critical reception it deserved, though the books were popular with readers. Fifteen years ago he suddenly gave up writing, exhausted, he said, of things to say. He took up painting instead and repaired Victorian chairs. At the end of March this year, after fifty years of marriage, Ruth died after a long illness. At her funeral Richard read a paragraph from his autobiography, describing his love for her at first sight. It was a stunning moment in the quiet chapel, charged with love and an aching sadness. Just under four weeks later he died too, suddenly and shockingly. His heart was broken, his daughters say.

###

John Middleton Murry

John Middleton Murry, who has died suddenly aged 75, grew up in the literary shadow of his famous father, but he was an excellent novelist in his own right and in later years became an admired and popular science fiction writer.

“… Another John Middleton, ye gods!” said D.H. Lawrence, when he heard of John Jnr’s birth in 1926. His grandmother nicknamed the baby Colin, which years later was to provide a semi-pseudonymous byline for his books.

John’s mother was Violet Le Maistre, JMM Snr’s second wife after Katherine Mansfield, who modelled herself to excess on her predecessor. Not only did Violet physically resemble Mansfield, she wrote stories in that mould. When John was eight months old, she contracted pulmonary tuberculosis. JMM Snr recorded in his diary that she broke the news with the words, “I’m so glad! How could you love me without this?” She died just before John’s fifth birthday. The turbulent years that followed this early bereavement are recorded in the first volume of Murry’s autobiography, One Hand Clapping. Two stepmothers came after: the first was Betty, a woman of immense verbal and physical violence who for many years terrorised both John and his father. John was sent as a boarder to Rendcomb College, the independent progressive school in Gloucestershire, avoiding some but not all of the domestic upheavals.

In 1944 John joined the Royal Navy, a spell in uniform that his father treated unexpectedly benignly, perhaps an early hint of his own sudden move away from pacifism that was to come in the 1950s. John originally applied to join the Fleet Air Arm as a pilot, but he was turned down on the grounds that his eyesight was deficient. The RN Commander who announced the rejection was a man with a ferocious squint, an irony that John hilariously remembered for years after the event. He spent his war service as a lowly rating, narrowly spared a posting to the Far East by the sudden capitulation of the Japanese. After the war he went to Brasenose College, Oxford, reading the Anglo-Saxon he hated and the English he loved. The poetry of Sidney Keyes had an early impact on his life; later came John Donne and William Wordsworth. Donne, he said later, “provided me with a touchstone of excellence, living proof that intensity of feeling was the very life-blood of great literature”. The die was cast. With some cautious encouragement from his father, John had begun writing in his teens: short stories, critical essays, a few poems. Little of this early work survives in print, and his first novel was not published until 1958. Other matters had to be settled first. He met his wife Ruth Jezierski in 1948 and they married a year later. Less than an hour before the wedding ceremony he was still inside B.N.C., well lubricated with brandy, gabbling his way through his vivas; he passed on compassionate grounds, he decided later.

The first novel was called The Golden Valley. John showed it to his father soon after he finished it in 1954, seeking what he saw as the ultimate stamp of approval. JMM Snr was harsh: he complained that its style, seemingly autobiographical, would identify him as the protagonist and because ‘Betty’ was depicted sympathetically, an unfavourable light would be thrown on him. John was crushed by this self-serving response and by the time of his father’s death in 1957 the wound had hardly healed.

Three more novels as Colin Murry followed. The last appeared in 1972. They are all now long out of print, and while their depiction of honest emotion might not be fashionable in these more cynical times, the clarity of the prose and purity of language ensure they have dated hardly at all. They are long overdue for new editions.

Streaks of fantasy ran through at least two of these novels, so it’s no surprise that he was to turn to science fiction. Another byline was chosen for the new career: Richard Cowper. For several years the Middleton Murry heritage was, perhaps unsurprisingly, put to one side, and ‘Cowper’ made his way into the hidebound SF genre as a new writer. Responses were mixed: the readers were quickly beguiled by his subtle, lyrical and moving stories, but some of the SF critics couldn’t cope with a writer who worked with feelings rather than gadgets. The young Martin Amis, for instance, wrote a series of increasingly vicious reviews of the Cowper books. In private, John laughed Amis off: “He grew up with a famous father too!”

His best SF is found in the novel The Twilight of Briareus and the books in the White Bird of Kinship series, but most of his short stories were also remarkable. His work always stood out in the SF genre: he was anachronistic, but he dazzled with his elegant, precise, bountiful prose.

His wife Ruth died at the end of March 2002. At her funeral John read aloud the paragraph from his autobiography in which he described falling in love with her at first sight. It was beautiful and stunning, a poignant moment at the end of more than fifty years of marriage. Four weeks later John himself was dead. He leaves two adult daughters, Jacky and Helen, now forced to deal with this double blow.

###

Other books by Colin Murry include Shadows on the Grass (the sequel to One Hand Clapping) and Private View. Other novels by Richard Cowper include Clone, The Road to Corlay, and Time Out of Mind. Cowper’s best short stories can be found in The Custodians and Out There Where the Big Ships Go.